What is a Judeo-Christian?

The term Judeo-Christian is best known as an adjective describing the common basis of ethics and law between Judaism and Christianity which has shaped the societal foundation of Western countries, primarily the United States of America. My use of the term as both an adjective and a noun provides continuity between this traditional understanding and the recognition of a truth which has existed for two millennia but has been ignored by the whole world: that Christianity and Judaism are essentially two branches of the same religion.

Certainly, this statement has to be qualified: virtually no one in either the mainline Christian or Jewish communities would agree with this idea at face value; but the evidence is impossible to ignore when the facts are analyzed. The problem is simply that post-Second Temple Talmudic Judaism and “traditional” Christianity have grown so far apart that the commonalities are nearly unrecognizable. The vast majority of Jews maintain that one cannot accept Yeshua (Jesus) as the Messiah and still be a Jew, while Christians ask some very pointed questions, mainly surrounding the continued validity of Torah observance in daily life, which is (falsely) viewed as an opponent of a life of faith in God through Jesus Christ.

The facts remain that: we believe in the same God; we believe in the same foundational truths of the world; we have the same Scriptures; we share a common history—all of the founders of Christianity were themselves Jews, and they did not renounce or reject Judaism when they accepted Jesus as the Jewish Messiah.

Question: So what happened to split Judaism and Christianity apart?

To properly answer this question, we must first look at the background information:

From the very beginning, when YHWH called Abram out of Babylon into the land that would later be Israel, His covenant with Abram (here changed to Abraham) at the Oaks of Mamre declared that among YHWH’s many promises, which would be carried on through his son Isaac (and later through his grandson Jacob, whose name was changed to Israel), was that YHWH would be their God, and they would be His people. When YHWH rescued the children of Israel from slavery in Egypt 430 years later, He reaffirmed that covenant at Mt. Sinai, declaring that “…although the whole earth is Mine, you shall be for Me a kingdom of priests and a holy nation…” The word holy actually means separate—to be set apart for sacredness or purity. Deuteronomy 32:9 (Septuagint version) stated that the rest of the nations were portioned out to the ‘sons of God’—rebellious angels that were cast out of YHWH’s council to become the false ‘gods’ these nations would worship; but Israel was to be YHWH’s portion and inheritance.

God said that if the Israelites would keep His covenant, they would live in the land that God had given to them; and they would be blessed in all kinds of wonderful ways. However, if they failed to keep the covenant, they would bring all kinds of curses upon themselves and be kicked out of the land until such time that they repented and returned to God with all their hearts. The Israelites were commanded to stay separate from the ways of worship and other practices of the nations around them—and yet, they were called to be the light to the Gentiles: YHWH’s visible representatives in the earth, who would call the rest of the world’s inhabitants out of rebellion to repentance. This dichotomy caused Israel to live in a tension best defined by the later Christian colloquialism, ‘in the world, but not of it.’ However, this tension is easily thrown out of balance: we tend to either become so accepting of the world that we mix in to its unholy practices, or to separate ourselves from the world on an island of self-righteousness.

Of course, the history of Israel as shown in the Tanakh is a see-saw ride between these two extremes; but YHWH, being good, kind, patient, and slow to anger, merely warned and disciplined His people until finally in 586 B.C., the people had mixed into the idolatrous practices of their neighbors so thoroughly that He finally made good on His promise and exiled the people to Babylon for 70 years, but not before promising that He would make a New Covenant with them. It was during this time that the synagogue system was developed, where small groups of Jews would meet locally to study the Torah together and discuss how to interpret it. This was the beginning of the oral tradition from which the Talmud began to be collected. See What Do We Mean By ‘Torah Observance’? for more details.

When the people were allowed to return and rebuild the Temple under Nehemiah and the prophet Ezra, they made the decision to follow the Torah with their whole heart–even taking the harsh, drastic step of divorcing any non-Jewish wives they had married in violation of the Torah’s commandments (Ezra 10). They wanted to make sure that God had no reason to exile them again!

The Maccabean Crisis served to cement this xenophobic divide between Jews and their Gentile neighbors (see Hanukkah in the Holidays section, and this video for more details); they feared that any mixing between themselves and 'the nations' would bring God's wrath and possibly invite the end of Israel and the Jewish people. Quite simply, they were far more concerned about keeping hold of their land than they were about their mandate to reach the nations. So they decided that a Gentile could partake in the Sinai Covenant (the covenant with Abraham, Moses, and the people of Israel/Judah) as long as they were circumcised (if male) and followed Jewish traditions just as the Jews did; but even so, the Gentile converts remained on the outer rim of Jewish identity.

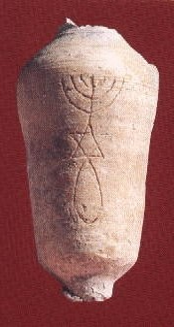

The menorah was the original symbol of Christianity

This is why many of the Jews were so thrown off by the New Covenant inaugurated by the death, resurrection, and priesthood of Jesus. The earliest followers of Jesus (ALL of whom were Jews) very quickly began to understand how all the prophecies of the Sinai Covenant applied to their experiences with Jesus and the Holy Spirit; they viewed everything that was happening to them as the release of the New Covenant within the confines of Judaism. Even Simon Peter was bewildered, however, when God released the Holy Spirit on a Roman Gentile family who believed in God but were not yet following the Torah or the Jewish traditions surrounding it. It was as if God Himself was tossing His own requirements aside. A debate ensued: on one side, the pro-proselyte conversion group could not separate from oral tradition as the standard of God’s covenant.

On the other hand, the Holy Spirit Himself clearly chose to rest on these Gentile people the same way He had on the Jewish believers in Jesus, showing no partiality as to their national origin or practice of Jewish ritual; why should they be required to undergo proselyte conversion if God had accepted them without doing so? Consequently, these all-Jewish leaders of early Christianity came up with a compromise at what became known as the Council of Jerusalem (see Acts 15): they asked that the Gentile believers in Jesus abstain from sexual immorality, meat that was sacrificed to idols, meat from animals that were strangled, and from eating blood, which was a minimal starting point from which these Gentiles would learn about YHWH. (These ideas appeared to be taken from the so-called 'Noahide Laws', the observance of which many Jews believe are the requirement for Gentiles to be considered righteous. See ‘What Do We Mean by Torah Observance?’ for more details.)

- ...is not like the Sinai Covenant in that there are no more blood sacrifices, special methods for approaching God, or atonement rituals performed for uncleanness, because Jesus Himself became the perfect sacrifice once for all time.

- ...internalizes the moral values of the Torah as written in the first five books of the Bible by relationship with God as our Father, activated through our acceptance of Jesus, and empowered by the Holy Spirit as opposed to simply presenting the values as the standard of living. In short, God takes that standard and He Himself works to produce it in us.

- ...is a covenant where all persons can have the same knowledge of God, because Jesus Himself has become our Eternal High Priest; no more priests are needed.

The compromise at the Council of Jerusalem did not work: the controversy continued, rife with traditional prejudices between Jews and Gentiles. Even Paul suggested in his writing to the Romans a deviation from the edict of the Jerusalem Council, favoring the idea that those with stronger faith can eat any kind of meat without it being credited as sin. On the other end of the spectrum, the extreme members of the pro-Jewish group continued to insist that these new Gentile believers undergo B’rit Milah and strictly follow the ‘oral Torah’; they were labeled 'Judaizers' by Paul and the two were in constant battle. This first schism of the church, fueled by a century and a half of previous divisions between Hellenistic and Hebraic Jews due to the Maccabean Crisis, was a fissure which slowly widened along the line between Jew and Gentile into the first three centuries A.D.

Not helping the matter was the fact that after the destruction of the Jewish Temple and diaspora of the Jews in A.D. 70, Gentile believers began to believe that the destruction of the Temple was a sign that God had abandoned the Jews. Meanwhile, the Jewish believers in Messiah continued to worship alongside the Pharisees in the synagogues; but the division between Messianic and non-Messianic Jews came during the Bar-Kochba revolt when Rabbi Akiva declared Shimon bar-Kochba to be the Messiah. Obviously, those Jews who believed Jesus to be the Messiah could not join themselves to this movement, and as the fighting grew fierce with the Romans, most of the Jewish believers fled to Pella in what is now Jordan, while Gentile Christians simply distanced themselves even further from the Jews to avoid persecution. See The Major Factors of the Split between Judaism and Christianity for more details.

After the revolt, which left Israel completely decimated, the Messianic Jews either became absorbed into Gentile Christian communities, or further traveled into the old Persian area beyond the reach of the Romans, where they survived until the rise of Islam in the 7th century A.D (See ‘Is Judeo-Christianity New?’ below). This left the Pharisees (the main group opposing Jesus in His lifetime) to become the dominant Western influence in post-Second Temple Judaism; indeed, modern Talmudic Judaism takes its teachings directly from the Pharisees. Where for the first 100 years, Gentile believers in Jesus were often discriminated against by Jewish ones, the tables turned after the first century as more and more Gentiles became Christian in the West; by the 300’s A.D., Jewish believers were far in the minority in the West, and general anti-Jewish rhetoric boiled to the surface.

Though this division certainly was tragically marked with violence and racism on both sides of the aisle, each still generally recognized the Jewish foundation of Christianity. This changed very suddenly, however, when Constantine the Great became Emperor of Rome in 312 A.D. The final break between Judaism and Christianity occurred as Constantine and his successors instituted a new form of Christianity over a 52-year period which deliberately and actively divorced itself from its Jewish roots, and instead was infused with elements of a Greco-Roman version of Babylonian paganism. This new hybrid became what would now be considered “traditional” Christianity; but it is radically different from what the founders of Biblical Christianity believed and practiced. Only the ‘brain stem’ of Biblically Christian thought and doctrine survived in the Nicene and Apostle’s Creeds. Prior to Constantine, Christianity was widely regarded by all persons to be a Jewish sect—even by Jews who did not believe Jesus was the Messiah; after the Constantinian revolution, however, Christianity was perceived as a totally separate religious system.

Question: Are you then seeking to ‘heal the rift’ between Christians and Jews?

In the light of this history marked by hatred and persecution, Talmudic Judaism and Constantinian Christianity cannot be reconciled except perhaps to tolerate each other from a distance. For those seeking authentic Biblical faith as YHWH and the founders of Christianity intended, however, the obvious antidote for this condition is to re-establish the connection between Judaism and Christianity in the Jewish foundation of the New Covenant. Those who understand this believe that this is not only necessary, but is prophesied to occur by the Apostle Paul in Romans 9-11. Not only are we seeking to heal the rift, we are seeking to restore the ‘one new man’ as the people of God (Ephesians 2:11-22).

As a noun then, my use of the term Judeo-Christian describes a Christian person who believes that authentic Christianity is simply the fulfillment of the Jewish New Covenant described in the Tanakh, specifically referenced in Jeremiah 31:31-34, Ezekiel 36:22-38; and by Jesus in the Gospels as He celebrated the Passover before His death (Matthew 26:26-29, Mark 14:22-26, Luke 22:19-20, and retold in 1 Corinthians 11:23-26). As such, Christianity can only be truly understood in its original Jewish context. Simply put, a Judeo-Christian is a person who sees Christianity from the lens of its original Jewish perspective and seeks to practice Biblical faith from this vantage point.

The Bible is the foundation of both covenants; and so when reading and interpreting the Bible, one can only derive its meaning by examining it from its original perspective. The Scriptures were written by God through Jewish authors to primarily a Jewish audience; and therefore, as Judeo-Christians, all of our theological interpretations must be based in the framework of Biblical Judaism. The Constantinian church, in contrast, has developed its theology as a ‘best-guess’ approach to the Scriptures in direct rejection of the Jewish context, applying instead the thought processes and context of Greco-Roman pagan culture and philosophy.

Question: If you believe that true Biblical Christianity is a form of Judaism, why wouldn't you want to simply be Jewish?

This depends on one’s definition of both Judaism and Christianity. Post-Second Temple Talmudic Judaism has deviated from Biblical Judaism as much as Constantinian Christianity’s deviation from Biblical Christianity; so we cannot be defined by either moniker. The website of one congregation used this phrase to describe themselves: "We consider ourselves to be both Jewish and Christian, but neither 'traditionally Jewish' nor 'traditionally Christian'." On the other hand, Biblical Judaism is the foundation of both, and there we find our commonality and the truth of our message. Therefore, the Judeo-Christian seeks to reestablish concepts and practices that are consistent with Biblical values specifically related to a proper Jewish contextual understanding of worshipping God. This does not mean that one must necessarily worship in Hebrew or by following Jewish cultural idioms; it is the context behind these things that allows us to see the blueprint God has for his interactions with man. At this level, our belief is inherently Jewish; it cannot be separated from Judaism.

Anointing oil jar used by 1st century church of Jerusalem with Messianic Seal. Found in a Jerusalem grotto in the 1960's.

Question: Is Judeo-Christianity new?

No, Judeo-Christianity is not new. Not only did the original Christians consider themselves to be practicing Jews, Judeo-Christianity spread out from the church in Jerusalem eastward, mainly in the Eastern Roman Empire and the area of the Old Persian Empire as far away as India. Despite Constantine’s edicts in the 4th century, Judeo-Christianity survived from a position of strength all the way through the 5th century, with the last vestiges of its influence falling to the Islamic caliphates in the 7th century. So Judeo-Christianity is a modern resurrection of the most ancient form of Christianity in existence; in this way, we cannot be separated from Christianity either.

Question: Is Judeo-Christianity a denomination or sect?

No, Judeo-Christianity is an expression of the Christian faith. It seeks to embody the original Jewish story, truths, and principles upon which the Christian faith was founded when taking the original cultural context into account.

Question: Are there any established groups practicing Judeo-Christianity today?

Perhaps the group most similar to Judeo-Christian expression would be Messianic Judaism, which consists of various groups of mostly Jews who recognize Jesus as the Jewish Messiah. They have been accused in the past of being Baptist proselytizers masquerading as Jews for the purpose of enticing Jews to leave Judaism and convert to Christianity; nothing could be further from the truth. Instead, they truly worship as Jews in the traditions of their ancestors while simply sharing the Christian belief that Jesus is the Jewish Messiah and the fully divine, yet fully human Son of God. As such, they believe He is the fulfillment of Jewish prophecy and the focal point on which the history of Israel swings. A 2008 decision by the Supreme Court of the State of Israel allowed Messianic Jews to make aliyah if they can show maternal Jewish ancestry, but were not bar-mitzvahed as a Jew and then voluntarily accepted Jesus as the Messiah. It is a battle which continues to swing first one way, then the other. The hope, of course, is for Jewish recognition of Messianic Judaism as an official Jewish sect, legalizing it in the eyes of the Jewish people.

Another movement that has exploded in growth over the last couple of decades is the Hebrew Roots movement (now often referred to as the ‘Torah Observant’ movement). This is a loosely affiliated group of mainly Gentile Christians who have recognized the Jewish foundation of Christianity and are seeking to embrace Jewish practices in order to increase their understanding of the Christian faith. Unfortunately, many within this group have a skewed view of the Torah, and so they are often combative against both mainstream Christian and mainstream Jewish groups. Furthermore, some of them are fast becoming a modern-day version of the Ebionites, a first-century group of mainly Hebrew persons that accepted Jesus as a non-divine Messiah; they rejected the writings of Paul the Apostle, and believed that a post-Second Temple Jewish application of Torah observance was essential to salvation.

Like the Hebrew Roots movement, Judeo-Christianity seeks to understand the Jewish context in order to fully comprehend the Biblical understanding of what Christianity should be; and there are certain Jewish practices that are wholly Biblical and should be resurrected in the life of the Judeo-Christian. Unlike the Hebrew Roots movement, however, we fully accept the Messianic and Christian doctrine that Jesus is both fully human and fully divine, and we accept that Paul's writings are divinely inspired Holy Scripture (though they must be interpreted within the correct context—see Paul Misinterpreted? for more details). Furthermore, given the adaptation of the Torah to the atoning work of the Messiah concerning the priesthood, sacrifices, and penalties for sin, as well as the culturally universal and prophetically fulfilling nature of the New Covenant, there are other Jewish practices that we believe apply in principle or have practical but conceptual application to our lives rather than as stand-alone, literal mitzvot.

Overall, we could be described somewhat as a Gentile Christian counterpart to Messianic Judaism. Two major differences that might set us apart in practice from Messianic Jews are these: 1. Though we share the vast majority of the beliefs and perspectives of Messianic Judaism, we are not necessarily ethnically Jews, nor are we seeking to become Jewish in a cultural sense as much as we are simply seeking to understand and live out our Christian faith in its true Jewish context. We may practice some Jewish traditions, language, rituals, and cultural idioms that we find particularly helpful or simply beautiful expressions of our covenant relationship with YHWH, but they are not binding on us as commandments. 2. Many Messianic Jews teach a separation between Jews and Gentiles, citing the Noahide Laws as the basis of their argument; they believe that Jews must follow the Torah to the letter, but Gentiles have a lesser calling and must abide by only the Noahide Laws as part of life in Messiah. In contrast, Judeo-Christianity teaches that Gentile followers of Jesus are fully adopted—‘grafted’ into the nation of Israel (Romans 11, Ephesians chapters 2 and 3), and that God's instruction in the Torah applies to everyone—what is good for the goose is good for the gander. God has broken down the wall of separation between Jew and Gentile, and he has created 'one new man' from the two. The Torah as interpreted through the life, fulfillment, and priesthood of Jesus Christ applies to all believers. (See What Do We Mean by ‘Torah Observance’? for more details.)

Some of the 'bigger' concepts that were lost in the Romanization of Christianity that we would practice would be:

- The restoration of Shabbat. This involves far more than changing the day of corporate worship back to Saturday as originally prescribed by God, though this is part of the issue. Shabbat is about living a shared life with God and His family in shalom—that is, perfect worship, rest, peace, love, and fellowship.

- The restoration of blessing. The mandate of the people of God is to become a kingdom of priests and a holy nation. As priests of God to the world, we have been delegated all of the authority that Jesus was given by the Father, and we are admonished to bless instead of curse. Living a lifestyle of blessing involves a total transformation from self-worship to God-worship—which is really self-sacrificial love for God and others.

- The restoration of family. God revealed Himself through a family-nation; He established the family as the building block of society and the model for His church. The Greco-Roman model of society is institutional and academic by contrast. Therefore, the church should operate as a family rather than as a business or academic institution. In the Hebraic context, learning takes place by shepherding—mentoring and apprenticeship in the context of a true friendship instead of the sterile transfer of information through oration and classroom instruction.

- The restoration of our understanding of the covenants. A covenant, from a Biblical perspective, is an unbreakable alliance—like a marriage. In both covenants, God declares that He will be our God and we will be His people; tucked into these declarations are certain promises and responsibilities. The Sinai Covenant, made with Abraham and arbitrated by Moses, established Israel as the people of God, a kingdom of priests, and a holy nation. The New Covenant, established with David and arbitrated by Jesus, rescued God’s people, united His people to Himself, and empowered His people to live the kingdom mandate. Both covenants are with the people of Israel. Gentiles who believe were admitted to the Sinai Covenant through circumcision; and to the New Covenant by Jesus Christ, where we have been grafted into the nation of Israel.

- The restoration of a proper understanding of the Torah of Moses as it relates to Christ's priesthood with relation to the New Covenant: how the Torah has been changed rather than abolished according to Hebrews 7 and Matthew 5. The priestly requirements of the Torah have their continuous fulfillment in Jesus’ sacrifice and eternal High Priesthood; but the moral standard of the Torah remains, becoming the evidence or fruit of the Holy Spirit's work in our lives. When Paul says we are ‘no longer under the Law’, he means that we no longer have to offer blood sacrifices because Jesus has become our Passover Lamb; he does not mean that we can behave however we wish.

- The restoration of the original story and Biblical heritage of our faith. This encompasses a great many issues and represents a wide-scale paradigm change from the Constantinian church. While there is much that is good in the 2000-year history of the Constantinian church that we can celebrate and from which we can glean, there are some elements that are completely based in paganism and even myth, which must be completely disregarded or restored to a Biblical understanding. The most obvious example is surrounding the celebration of Jesus’ death and resurrection, which fulfilled the Jewish Levitical Feasts of Passover and Firstfruits respectively. The celebration of these festivals was purposely changed at the Council of Nicaea in 325 A.D. by Constantine himself and replaced with the pagan festival of Easter, which pays homage to the Babylonian goddess Ishtar (Astarte, Ashteroth, Isis, Easter). Neither Christians nor Jews have any business calling anything by the name of a foreign goddess; instead, we should restore the celebration of the Passover and Firstfruits in their New Covenant Jewish context. Likewise, Christmas was established to coincide with the pagan festivals of Yule and Saturnalia. While it is helpful to celebrate the Incarnation of Jesus, scholars today show that Jesus’ birth did not occur on December 25th; most likely this occurred in autumn, perhaps even coinciding with the Jewish Festival of Sukkot (Feast of Tabernacles)—which would make sense from a prophetic standpoint, given that the name Tabernacles means ‘dwelling’ and that one of the names of Jesus is ‘Immanuel’—God with us.

- The restoration of a Biblically-centered body of truth. We believe that the Bible, both the Tanakh (the ‘Old Testament’) and the B’rit Chadashah (the ‘New Testament’) are the divinely inspired Word of God. Furthermore, the Bible shows that God is ultimately revealed in the person of Jesus Christ, also called ‘the Word’. While not equal in substance, they are equal in message. They mutually interpret each other, and serve as our final rule of faith and practice. There are many practices in both rabbinical Judaism and Constantinian Christianity that are neither Biblically-based, nor have the heart of Christ. We seek to allow our theology and practice to be informed by a proper interpretation of the Scriptures.

Some general questions the Judeo-Christian asks him or herself as they go about their daily practice of faith are:

- If God commanded His people to do something in a certain way, why would we seek to do it differently?

- Why would we want to put our own spin on something, thinking that somehow our own contrived context works better than the Jewish context in which God revealed Himself?

- If God has not specifically commanded something in the Bible, why are we doing it? There may not be anything wrong with what we are doing, but what is our motivation for doing what we do?”

Let’s ask God what He thinks by looking at His revealed Word in the Bible filtered through the life of Jesus Christ and draw our conclusions from that instead of allowing our traditions or culture to inform our theology.